Yesterday I gave a super duper high level 12 minutes presentation

about some issues of bias in AI. I should emphasize (if it's not

clear) that this is something I am

not an expert in; most of

what I know is by reading great papers by other people (there is a

completely non-academic sample at the end of this post). This blog

post is a variant of that presentation.

Structure: most of the images below are prompts for talking

points, which are generally written below the corresponding image. I

think I managed to link all the images to the original source (let me

know if I missed one!).

Automated Decision

Making is Part of Our Lives

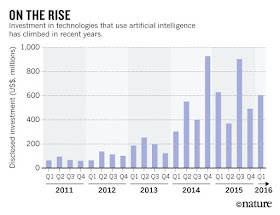

To me, AI is largely the study of

automated decision making,

and the investment therein has been growing at a dramatic rate.

I'm currently teaching undergraduate artificial intelligence. The

last time I taught this class was in 2012. The amount that's changed

since there is incredible. Automated decision making is now a part of

basically everyone's life, and will only be more so over time. The

investment is in the billions of dollars per year.

Things Can Go Really

Badly

If you've been paying attention to headlines even just over the

past year, the number of high stakes settings in which automated

decisions are being made is growing, and growing into areas that

dramatically affect real people's real life, their well being, their

safety, and their rights.

This includes:

This is obviously just a sample of some of the higher profile work

in this area, and while all of this is work in progress, even if

there's no impact today (hard to believe for me) it's hard to imagine

that this isn't going to be a major societal issue in the very near

future.

Three (out of many)

Source of Bias

For the remainder, I want to focus on three specific ways that

bias creeps in. The first I'll talk about more because we understand

it more, and it's closely related to work that I've done over the

past ten years or so, albeit in a different setting. These three are:

-

data collection

-

objective function

-

feedback loops

Sample Selection Bias

The standard way that machine learning works is to take some

samples from a population you care about, run it through a machine

learning algorithm, to produce a predictor.

The magic of statistics is that if you then take new samples from

that same population, then, with high probability, the predictor will

do a good job. This is true for basically all models of machine

learning.

The problem that arises is when your population samples are from a

subpopulation (or different population) for those on which you're

going to apply your predictor.

Both of my parents work in marketing research and have spent a lot

of their respective careers doing focuses groups and surveys. A few

years ago, my dad had a project working for a European company that

made skin care products. They wanted to break into the US market, and

hired him to conduct studies of what the US population is looking for

in skin care. He told them that he would need to conduct four or five

different studies to do this, which they gawked at. They wanted one

study, perhaps in the midwest (Cleveland or Chicago). The problem is

that skin care needs are very different in the southwest (moisturizer

matters) and the northwest (not so much), versus the northeast and

southeast. Doing one study in Chicago and hoping it would generalize

to Arizona and Georgia is unrealistic.

This problem is often known as

sample selection bias in the

statistics community. It also has other names, like covariate shift

and domain adaptation depending on who you talk to.

One of the most influential pieces of work in this area is the

1979 Econometrica paper by James Heckman, for which he won the 2000

Nobel Prize in economics. He's pretty happy about that! If you

haven't read

this

paper, you should: it's only about 7 pages long, it's not that

difficult, and you won't believe the footnote in the last section.

(Sorry for the clickbait, but you really should read the paper.)

There's been a ton of work in machine learning land over the past

twenty years, much of which builds on Heckman's original work. To

highlight one specific paper: Corinna Cortes is the Head of Google Research New York and has had

a number of excellent papers on this topic over the past ten years.

One in particular is

her

2013 paper in Theoretical Computer Science (with Mohri) which

provides an amazingly in depth overview and new algorithms. Also a

highly recommended read.

It's Not Just that Error

Rate Goes Up

When you move from one sample space (like the southwest) to

another (like the northeast), you should first expect error rates to

go up.

Because I wanted to run some experiments for this talk, here are

some simple adaptation numbers for predicting sentiment on Amazon

reviews (data due to

Mark

Dredze and colleagues). Here we have four domains (books, DVDs,

electronics and kitchen appliances) which you should think as

standins for the different regions of the US, or different

demographic qualifiers.

The figure shows error rates when you train on one domain

(columns) and test on another (rows). The error rates are normalized

so that we have ones on the diagonal (actual error rates are about

10%). The off-diagonal shows how much additional error you suffer due

to sample selection bias. In particular, if you're making predictions

about kitchen appliances and

don't train on kitchen appliances,

your error rate can be more than two times what it would have been.

But that's not all.

These data sets are balanced: 50% positive, 50% negative. If you

train on electronics and make predictions on other domains, however,

you get different false positive/false negative rates. This shows the

number of test items predicted positively; you should expect it to be

50%, which basically is what happens in electronics and DVDs.

However, if you predict on books, you

underpredict positives;

while if you predict on kitchen, you

overpredict positives.

So not only do the error rates go up, but the way they are

exhibited chances, too. This is closely related to issues of

disparate impact, which have been studied recently by many people,

for instance by

Feldman,

Friedler, Moeller, Scheidegger and Venkatasubramanian.

What Are We Optimizing

For

One thing I've been trying to get undergrads in my AI class to

think about is what are we optimizing for, and whether the thing

that's being optimized for is what is best for us.

One of the first things you learn in a data structures class is

how to do graph search, using simple techniques like breadth first

search. In intro AI, you often learn more complex things like A*

search. A standard motivating example is how to find routes on a map,

like the planning shown above for me to drive from home to work

(which I never do because I don't have a car and it's slower than

metro anyway!).

We spend a lot of time proving optimality of algorithms in terms

of shortest path costs, for fixed costs that have been given to us by

who-knows-where. I challenged my AI class to come up with features

that one might use to construct these costs. They started with

relatively obvious things: length of that segment of road, wait time

at lights, average speed along that road, whether the road is

one-way, etc. After more pushing, they came up with other ideas, like

how much gas mileage one gets on that road (either to save the

environment or to save money), whether the area is “dangerous”

(which itself is fraught with bias), what is the quality of the road

(ill-repaired, new, etc.).

You can tell that my students are all quite well behaved. I then

asked them to be evil. Suppose you were an evil company, how might

you come up with path costs. Then you get things like: maybe

businesses have paid me to route more customers past their stores.

Maybe if you're driving the brand of car that my company owns or has

invested it, I route you along better (or worse) roads. Maybe I route

you so as to avoid billboards from competitors.

The point is: we don't know, and there's no strong reason to a

priori assume that what the underlying system is optimizing for is my

personal best interest. (I should note that I'm definitely not saying

that Google or any other company is doing any of these things: just

that we should not assume that they're not.)

A more nuanced example is that of a dating application for, e.g.,

multi-colored robots. You can think of the color as representing any

sort of demographic information you like: political leaning (as

suggested by the red/blue choice here), sexual orientation, gender,

race, religion, etc. For simplicity, let's assume there are way more

blue robots than others, and let's assume that robots are at least

somewhat homophilous: they tend to associate with other similar

robots.

If my objective function is something like “maximize number of

swipe rights,” then I'm going to want to disproportionately show

blue robots because, on average, this is going to increase my

objective function. This is especially true when I'm predicting

complex behaviors like robot attraction and love, and I don't have

nearly enough features to do anywhere near a perfect matching.

Because red robots, and robots of other colors, are more rare in my

data, my bottom line is not affected greatly by whether I do a good

job making predictions for them or not.

I highly recommend reading

Version

Control, a recent novel by Dexter Palmer. I especially recommend

it if you have, or will, teach AI. It's fantastic.

There is an interesting vignette that Palmer describes (don't

worry, no plot spoilers) in which a couple engineers build a dating

service, like Crrrcuit, but for people. In this thought exercise, the

system's objective function is to help people find true love, and

they are wildly successful. They get investors. The investors realize

that when their product succeeds, they lose business. This leads to a

more nuanced objective in which you want to match

most

people (to maintain trust), but not perfectly (to maintain

clientèle). But then, to make money, the company starts selling its

data to advertisers. And different individuals' data may be more

valuable: in particular, advertisers might be willing to pay a lot

for data from members of underrepresented groups. This provides

incentive to actively do a worse

job than usual on such clients. In the book, this thought exercise

proceeds by human reasoning, but it's pretty easy to see that if one

set up, say, a reinforcement learning algorithm for predicting

matches that had long term company profit as its objective function,

it could learn something similar and we'd have no idea that that's

what the system was doing.

Feedback Loops

Ravi Shroff recently visited the CLIP lab and talked about his work

(with Justin Rao and Shared Goel) related to stop and frisk policies in New York. The setup here is that the “stop and frisk”

rule (in 2011, over 685k people were stopped; this has subsequently been declared unconstitutional in New York) gave police

officers the right to stop people with much lower thresholds than probable cause, to try

to find contraband weapons or drugs. Shroff and colleagues focused on

weapons.

They considered the following model: a

police officer sees someone behaving strangely, and decide that they

want to stop and frisk that person. Before doing so, they enter a few

values into their computer, and the computer either gives a thumbs up

(go ahead and stop) or a thumbs down (let them live their life). One

question was: can we cut down on the number of stops (good for

individuals) while still finding most contraband weapons (good for

society)?

In this figure, we can see that

if the system thumbs downed 90% of stops (and therefore only 10% of

people that police would have

stopped get stopped), they are still able to recover about 50% of the

weapons. With stopping only

about 1/3 of individuals, they are able to recover 75% of weapons.

This is a massive

reduction in privacy violations while still successfully keeping the

majority of weapons off the streets.

(Side note: you might worry about sample selection bias here,

because the models are trained on people that the policy did actually

stop. Shroff and colleagues get around this by the assumption I

stated before: the model is only run on people who policy have

already decided are suspicious and would have stopped and frisked

anyway.)

The question is: what happens if and when such a system is

deployed in practice?

The issue is that policy officers, like humans in general, are not

stationary entities. Their behavior changes over time, and it's

reasonable to assume that their behavior would change when they get

this new system. They might feed more people into the system (in

“hopes” of thumbs up) or feed fewer people into the system

(having learned that the system is going to thumbs down them anyway).

This is similar to how the sorts of queries people issue against web

search engines change over time, partially because we learn to use

the systems more effectively, and learn what to not consider asking a

search engine to do for us because we know it will fail.

Now, once we've (hypothetically) deployed this system, it's

collecting its own data, which is going to be fundamentally different

from the data is was originally trained one. It can continually

adapt, but we need good technology for doing this that takes into

account the human behavior of the officers.

Wrap Up and Discussion

There are many things that I didn't

touch on above that I think are nonetheless really important. Some

examples:

-

All the example “failure”

cases I showed above have to do with race or (binary) gender. There

are other things to consider, like sexual orientation, religion,

political views, disabilities, family and child status, first

language, etc. I tried and failed to find examples of such things,

and would appreciate pointers. For instance, I can easily imagine

that speech recognition error rates skyrocket when working for users

with speech impairments, or with non-standard accents, or who speak

a dialect of English that not the “status quo academic English.”

I can also imagine that visual tracking of people might fail badly

on people with motor impairments or who use a wheelchair.

-

I am particularly concerned

about less “visible” issues because we might not even know. The

standard example here is: could a social media platform sway an

election by reminding people who (it believes) belong to a

particular political party to vote? How would we even know?

-

We need to start thinking about

qualifying our research better with respect to the populations we

expect it to work on. When we pick a problem to work on, who is

being served? When we pick a dataset to work on, who is being left

out? A silly example is the curation of older datasets for object

detection in computer vision, which (I understand) decided on which

objects to focus on by asking five year old relatives of the

researchers constructing the datasets to name all the objects they

could see. As a result of socio-economic status (among other

things), mouse means the thing that attaches to your computer, not

the cute furry animal. More generally, when we say we've “solved”

task X, does this really mean task X or does this mean task X for

some specific population that we haven't even thought to identify

(i.e., “people like me” aka the

white

guys problem)? And does “getting more data” really solve the

problem---is more data always good data?

-

I'm at least as concerned with

machine-in-the-loop decision making as fully automated decision

making. Just because a human makes the final decision doesn't mean

that the system cannot bias that human. For complex decisions, a

system (think even just web search!) has to provide you with

information that helps you decide, but what guarantees do we have

that that information isn't going to be biased, either

unintentionally or even intentionally. (I've also heard that, e.g.,

in predicting recidivism, machine-in-the-loop predictions are worse

than fully automated decisions, presumably because of some human

bias we don't understand.)

If you've read this far, I hope you've

found some things to think about. If you want more to read, here are

some people whose work I like, who tweet about these topics, and for

whom you can citation chase to find other cool work. It's a highly

biased list.

-

Joanna Bryson (

@j2bryson), who

has been doing great work in ethics/AI for a long time and whose

work on bias in language has given me tons of food for thought.

-

-

-

Sorelle Friedler (

@kdphd), a

former PhD student here at UMD!, has done some of the initial work

on learning without disparate impact.

-

-

Hanna Wallach (

@hannawallach) is

the first name I think of for machine learning and computational

social science, and has recently been working in the area of

fairness.